- Home

- Noël Browne

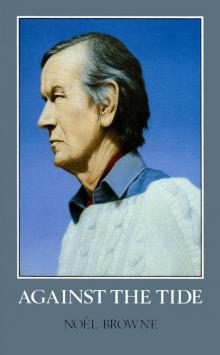

Against the Tide

Against the Tide Read online

Preface

Being neither a diarist nor a historian, I cannot claim that this book is a definitive history. It was written with some reluctance, and only after long consideration, in order to correct the inaccuracies of other accounts about a number of important incidents. The events recorded in these pages are the recollected memories of an eventful and at times a controversial life, throughout ‘the seven ages’, from childhood to old age, both in England and in Ireland.

Circumstances ordained that I should lead a nomadic, itinerant existence. I have collected no library, nor have I kept any records. For this reason, for occasional verification, I have had to call on the generosity and memories of my friends, for their recollection of shared events. Equally invaluable were the records of the relevant period in the State Paper Office in Dublin Castle. As so many students have found, I had the willing help at all times of Dr MacGiolla Coille, together with his painstaking staff. Jack McQuillan and his wife, Angela, were characteristically patient and helpfully critical. Jack, a one-time Clann na Poblachta deputy, generously put at my disposal all his memories of our joint experiences, as well as any papers he had kept. George Lawlor, my first Director of Elections, my good friend during all the years, and a onetime member of Clann na Poblachta, happily for both of us possesses a computer-like memory. He could not do too much for me. Fortunately, in his valuable library of books and papers, he had also carefully retained much of the literature put out by Clann na Poblachta at that time. All of this he allowed me to use. The dates, personalities, and events, so meticulously researched and collated by Katie Burns of Cork in her excellent thesis on the Mother and Child controversies, were an enormous help, for which I am very grateful.

In spite of the evidence of bulging libraries and the tens of thousands of authors, I found that, for me, it was not easy to write a book. The memories, so many of them, flood into one’s mind, events long forgotten, prised out of the unconscious, are pieced together to complete the resultant jigsaw. At the same time, order, sequence, chronology, need professional skills, so as to add shape and discipline to the story. That there is order, I am grateful to Ciaran Carty, a professional journalist who edited the script. To Deirdre Rennison, editorial secretary at Gill and Macmillan I offer my profound thanks for keeping the peace between myself, Michael Gill, and others. My lack of writing experience to such polished professionals, needed everyone’s understanding patience. I am grateful to the original publishers’ ‘reader’ of the manuscript, who, in its very early stage, gave it critical approval, and recommended that it be published.

To the O Fahertha family, our near neighbours on that isolated yet lovely Cloughmore peninsula on the Atlantic, both Phyllis and I would wish to acknowledge in gratitude their acceptance of the wanderers returned at last to their roots in the West and for the peace which made our work on the books and our life there so pleasurable.

In the end, to myself and to that truly remarkable woman Phyllis my wife, remained the task of preparing the text. My manuscript was typed and re-typed repeatedly by Phyllis with, where needed, valuable critical suggestions. With consistent encouragement of my occasionally flagging energies, she was infinitely more than typist.

In the story of a life, of which over fifty years has been lived together, does my wife not become the joint author? In a just world, beneath its title, this book should have subscribed two names, Noël and Phyllis Browne.

Contents

Cover

Title page

Preface

Chapter 1: Childhood in Athlone

Chapter 2: Growing up in Ballinrobe

Chapter 3: Education in England

Chapter 4: Student Days

Chapter 5: Medical Practice

Chapter 6: Into Politics

Chapter 7: In Government

Chapter 8: Gathering Clouds

Chapter 9: The Mother and Child Scheme

Chapter 10: Crisis

Chapter 11: Resignation

Chapter 12: Cabinet Portraits

Chapter 13: Independent

Chapter 14: In Fianna Fáil

Chapter 15: Psychiatric Practice

Chapter 16: The Left in Ireland

Chapter 17: Leaving Labour

Chapter 18: Reflection

Copyright

About the Author

About Gill & Macmillan

List of Illustrations

1

Childhood in Athlone

CAGED, a sense of claustrophobic entrapment, surrounded by the vertical lines of bar-like legs. Table legs, legs of chairs and stools, legs of grownups, no way out; these are my earliest recollections, crouching under a table in the yellow darkness of an oil-lamp lighted room, entombed among the legs of those grownups who were at work around the table. I was forgotten by them, occupied as they were with their own frenetic manipulations, coiling in circles six blindingly white starched Irish linen collars into boxes, then closing over the pure white paper flaps, slipping on the precisely-fitting lid, adding that filled box to the pile already by the table. This work was done in addition to an already long hard day’s work at one of Derry’s treadmill shirt factories; keeping collar boxes filled improved baby’s chances of being fed.

The boxes I well remember, since I was given what I suppose was a damaged one to play with. They were virgin white inside, with two speckless flaps of white paper at the top. As befits a product of the Emerald Isle, even in the yellow oil-lamp light the outside was a shiny, grass green, a blindingly gay plaything for baby. But for the grownups it was the pretentious, brashly shining cardboard symbol of working class life over eastern and western Europe at that time, soon to be challenged by a socialist revolution.

My earliest daytime memory is of being held in the arms of a frightened woman, behind a half door which looked out into a stony yard. Holding on to me so hard that her arms pained me, she tried to throw a long flat stone — it could have been a whetstone — at the black rats which appeared to be threatening us.

We had moved from Waterford, where I was born on 20 December 1915. My father, unemployed and the unskilled son of a small farming family in Co. Galway, brought us shortly after my birth to Derry, where we lived for a time in the Bogside. He obtained work in one of the shirt factories.

Because my mother was a daily Communicant, and a devout Catholic, I attended daily Mass from an early age. I have come to believe that the notable intensity of religion and devotion to the Sacraments, by Irish and indeed all Catholic peasant women, as opposed to the relative indifference of the men, must have fear among its origins. There is a forlorn hope that the magic miracle of the Mass, or other Sacrament, will fend off that greatest single fear so many working class mothers know, the fear of the next pregnancy.

While I had no choice as a very small child in attending the Mass, I feared the departure of my mother when she left me to go to the Communion rails. Insecure as always, I would then cry my heart out, until fascinated into silence by the rich golden rays of light, which I learned to create with the altar candles seen through my tears. The frivolous futility of these, my private exotic visions, made crying seem to me neither to suit nor to answer my immediate needs, the loss of my mother.

My overt personal scars from Derry are an unreasonable fear of rats together with one permanently deaf ear and one damaged eye, the result of uncared-for measles. I did not return to the Bogside again until 1969, when I formed part of a Labour Party delegation sent to study the emergent violence. There are no happy memories of Derry for me.

In 1920, my father was offered the job of Inspector with the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. With no regrets whatsoever we left Derry and arrived in Athlone, where a good-sized house came with the job and where, until th

e death of my father in 1923, we lived our lives of precarious survival.

In terms of emotional and physical development we grew up in a one-parent family; our father was virtually never at home. Our mother, a lovely, slight-figured country girl, took on the heavy burden of child-bearing and rearing which contributed to her early death at the age of forty-two. The family consisted of Eileen, Jody, Martha, Kitty, myself, Una and Ruth. There was also Annie, who died in infancy of tuberculous meningitis.

My father, Joseph Browne, was, as his marriage picture shows, a tall moustached handsome man. He was a well-known middle distance runner, and the shelves on our old Victorian whatnot were covered with silver and gold medals, cups and other trophies.

The formal marriage portrait shows my parents as an elegant pair of happy young innocents eager for the years ahead together. They enjoyed amateur acting and ballroom dancing; he was particularly popular for his songs at the piano, and his extrovert personality. He is proud, elaborately coiffed, in a dress suit with a gold chain, wearing the gold medals he had won. My mother Mary Therese wears a circular fur hat framing her lovely face, and a tiny gold and pink enamel watch, a gift from the groom, on its slim gold muff chain. That watch still bears the dents of a teething child. There was, however, a second, later, picture, also taken in Athlone, which shows my father separately, with seven of his children. My mother was probably pregnant with my last sister, Ruth, to be born shortly after his death. Here he is, physically, a completely different man, in the last destructive phase of tuberculosis. Part Spanish on his father’s side, he is a dark, bonyfaced, black-eyed, shrunken man. He was to die soon afterwards. My inconsolable mother died some two years later. We children were then left homeless and penniless, as were and are so many unwanted children of primitive peasant societies such as ours was.

Even though the slow destruction of my family took place during our years in Athlone, my experiences there became the most settled and contented part of my young life. Athlone is set in the dead centre of Ireland with the river Shannon running through it. We spent our days playing just below the weir, on the small stony beach. The fluctuant river with its floods and its droughts and the noise of the weir became a constant heartbeat, conditioning my later adult obsession with the sea, its sounds, its tides, its pleasures and its dangers.

For the most part we played down by the Shannon, sailing unmanageable boats made by ourselves. In wet weather we were fortunate to have access to a builder’s yard belonging to a friend of ours named Duffy, who lived opposite our house in Irishtown. This became an idyllic world of fantasy within our other world. There were long, low, dark lofts, garrets, workshops, outhouses and what seemed to us children to be great mountains of sand and gravel, which we converted into strong points during our battles. Our play had unlimited scope for our imaginings. When we were tired, we listened to the stylised music of Mr Duffy’s old music box. I still recall those times whenever I hear the melody ‘La Barcarolle’.

It became the practice for us children to mimic the Civil War then being fought in all its real ferocity around us. We used catapults and pea-shooters, or simply threw pebbles at one another, ‘Shinners’ on one side and ‘Staters’ (the Duffys were a Free State family) on the other, from sand heap to gravel pit. I recall being in my special uniform, which included a protective steel white knobbed platecover, and receiving a direct hit on my luckily protected head — killed stone dead, no doubt, in real life — even though I was dug into a deep hole in the centre of a great mound of sand.

Athlone was an important garrison town with a substantial force of soldiers, originally British, now Irish, permanently stationed there. The sides taken up by us in our mock civil war — Staters, Republicans, or Irregulars — reflected the divisions of parental loyalties in the struggles all around us. It was the practice for the Irregulars to invade and harass the town, burning down an enemy property or carrying out a hit- and-run assassination. I watched with no understanding the exhilarating sight of the grocery store owned by the Brodericks, some fifty or sixty yards from our house, burning wildly during a winter’s night, sparks and smoke curling away on the wind into the night sky. Fear was transmitted to me from the grownups around because of the danger that the fire would spread along the row of tiny houses and include our own in the holocaust.

There had been a night like that long before. I was learning how to walk and was being helped by my father on our way up to Sweeney’s general shop a few hundred yards from our house. There was a hurried scattering of frightened men and women, well used by then to the ominous whine of the Black and Tan Crossley lorries. It was the practice for these British auxiliaries, a force of mercenaries who had fought in the 1914-18 war, to sweep through Irish towns and villages in their Crossley tenders, dressed in a motley of uniforms and armed with rifles and revolvers. They were protected from attack by wire cages over the back of the lorry, and by hostages taken from the local community. The hostages sat back to back on their long wooden forms in the centre of the lorry. Frightened, no doubt and often drunk, the Black and Tans shot at civilians out of a macabre sense of fun. My father on this occasion dragged me into his arms and ran up the few steps to reach the safety of Sweeney’s shop. There I found myself sitting on a heap of copper and silver coins and paper money in the centre of the small safe.

One night we were awakened abruptly by my father. He was angry, which surprised me since he was a very even-tempered man, and was abusing those outside the house. I recall hearing him mutter ‘if only I had a gun myself’. He ordered us all to lie down flat on the floor. We were in the front line in an ambush: an assassination attempt was being carried out by the Irregulars on a car full of Free State officers; these officers, based in Custume Barracks, used to visit Duffy’s house, directly opposite to ours. On this occasion, the senior officer and a young lieutenant were ambushed just as they drove away. We were in the heart of the ambush in our first floor bedroom, listening to much shouting and then shooting. Whether I imagined it or not, I recall hearing someone shout ‘don’t shoot’. This was followed by the sound of shooting, then the sound of men running up the lane beside our house. I heard the distinctive metallic clanging sound of the heavy iron gates to Kane’s field at the top of the laneway, and they were away.

The attackers did not ‘get’ the senior officer for whom they had set the ambush, General Seán MacEoin, known and admired by the rest of us as the ‘Blacksmith of Ballinalee’. Instead a young lieutenant lay dead in his own great pool of blood, which was still there on the following morning for us children to see, covered simply by a rough potato sack — Pearse’s ‘rich red blood, which so enhances the soil’. I was neither frightened nor revolted, but exhilarated.

At school the following day, I went over the sequence of the night’s killing again and again for my interested fellow pupils, the centre of attention for having had the front seat at an ambush and a killing, and with the bullet-scarred walls of our house to prove it. This awful example of man’s unique capacity to kill cruelly a fellow man, even the wrong man, simply appeared to us like a cinema show. The bodily agony of the wounded and dying was transmuted by a crude potato sack and the faded black patch of blood. Is this all a merciful protection for the young who must live out their lives among the ‘grown-up’ men and women in control of man’s destiny?

Twenty-five years later, an odd sequel was acted out in the Cabinet office in Merrion Street, after the formation of the first coalition government in 1948, when the members of the Cabinet met to be introduced to each other. I introduced myself to Sean MacEoin, who was to be Minister for Justice. The last time I had heard his voice was under the window of our bedroom on the night of the ambush outside Duffy’s nearly thirty years before. I told MacEoin that in my account to my schoolfriends I had attributed to him the shouted words, ‘don’t shoot’. It was generally believed by the public that in spite of being a soldier, with the soldier’s awful job of daily learning how to kill other men more cleverly, MacEoin was a gentle pe

aceful man, who greatly regretted the ‘split’. He neither wanted to kill, nor be killed. MacEoin replied that his instinct would have been to try to stop the shooting, but on both sides.

Possibly attempting to obliterate the unhappy memory, he then proceeded to show me how he had disarmed his British Army guard when he was a prisoner in Dublin Castle, during an abortive attempt made by Michael Collins to rescue him. He grabbed my right hand, no doubt what he would have called my revolver hand, and pinned it helplessly behind my back. Even then, in middle age, he was an extremely powerful blacksmith of a man.

I remember too seeing row after row of tricolour-covered coffins, side by side. To me they were just so many colourful outsize parcels, in a great room in some building. In these coffins were the remains of men shot in Custume Barracks by the Free State government as part of massive reprisals for the killing of Dáil deputy Sean Hales; they could not lie before the altar in St Mary’s, since the Republicans had been excommunicated. These grim white pine boxes, filled with the bodies of innocent youths who had been murdered, ‘the sow devouring her farrow’, left no shocked memory on my child’s mind. Why not leave the bullet-shattered, terrified, open-eyed, naked corpse exposed for the young such as myself to see, and to learn from it the folly of our ‘wiser and older’ leaders of church and state?

This flag which we looked at was the same national flag run up over the castle in Athlone, after the Union Jack was lowered, to signify our new freedom from the British Army. Standing with my father on Custume Bridge, I had happily watched them tramp out of our lives, to be replaced by our new Free State army. But had this freedom not been won by these same young men, now boxed carcases, shot by their own, not by the British? Incomprehensible grownups; a child must learn to accept without question or explanation the enigmatic contradictions of adult life.

Much later in a diary kept by Peadar Cowan, an officer in the Free State army in Custume Barracks, I read of the blindingly whimsical system whereby the victims were chosen for death: it was a simple process of taking a group of prisoners from each county. Between November 1922 and May 1923, seventy-seven Republican prisoners in all were to be executed without trial. Since these men had all been in custody at the time of the shooting of Hales and were known to be innocent of the assassination for which the reprisals were being carried out, their killing was indefensible. The most stunning experience for me was to read how Peadar, a parliamentary colleague of mine in later life, recounted the incident of the mass executions without showing any sense of horror, shock, guilt or concern whatever for the whole process or his own part in it. Yet Peadar was what is known in Ireland as ‘a devoutly religious man’.

Against the Tide

Against the Tide