- Home

- Noël Browne

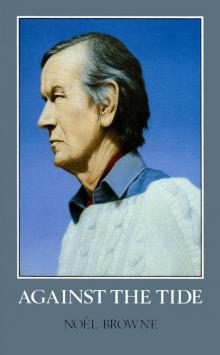

Against the Tide Page 4

Against the Tide Read online

Page 4

On the fair green on summer nights Toft’s roundabouts trumpeted out the distinctive hurdy-gurdy sounds of the steam organ into the normally silent night of Athlone’s residential area. Round and around gyrated and galloped the wide-eyed hobby horses, with flaring blood red nostrils, and streaming and flying white tails behind, racing into nowhere. At that fair my mother, a recluse by her avocation of housewife and mother, broke the rules to bring us to the roundabouts, and delighted us all and herself by winning a china teaset playing ‘hoopla’.

It was on the Ballymahon Road that I suffered an unexpected humiliation. Eileen, my eldest sister, had taught me to ride her heavy ladies’ iron bike. Still too small to reach the pedals and sit in the saddle, except when freewheeling precariously down the hill, I’d ride the bike standing on the pedals with an up and down hobby-horse movement, elbows higher than the hands on the handlebars, out to Molloys’ farm. I would leave it there while delivering the milk, and then ride it home again. This already precarious journey was further complicated by the can of skimmed milk Mrs Molloy would give me for my mother.

On my way down a small incline under the bridge I mistimed the follow through up-hill on the other side and was sent sprawling across the middle of the road, covered with milk. A man passing by came over to me, enquired how I was, helped me to pick up the bike and the empty can, and led me to the side of the road. My gentle soft-voiced friend murmured through my tears this information: ‘If you are patient, very patient, and take great care, the easiest way for you to catch a blackbird is to reach out with a pinch of salt in your fingers and carefully place the salt on his tail’. For some years I continued to wonder how this could be true. I learnt from this man that a lie like this in a good cause is sometimes permissible. At the same time, he contributed to my growing awareness about the fallibility of grownups.

Also on this road, I encountered for the first time the oppressor’s contempt for the oppressed. Myself and my sister Una were walking close to a high demesne wall. Seated on top of this wall were a boy and a girl, belonging to the big house. They must have seen us from a long way off, but they remained dead silent and unmoving. Because of the height of the wall, as well as our own tiny size, we did not see them until we were directly under where they sat. I looked up just in time to see a big outsize drop of spit spiralling down, impossible to avoid, onto my head and shoulders. For its infinitesimal size, it was a disproportionally painful experience wiping the spit away. We knew the name of the family, and as is the way on our tiny island I was to meet the boy years later when I was a medical student in Dublin’s Rotunda Maternity Hospital, where he had become an assistant master.

About a mile further along that Ballymahon Road, passing friends in a donkey cart gave me a lift home from Molloy’s one day. We meandered slowly home towards Athlone. On the pathway ahead of us came into sight a child-sized man, striding clumsily along, with long arms, long legs, and the short ugly twisted body of a hunchback. It was my brother Jody. There were already three of us on the narrow plank, stretched between the sides of the donkey cart. The ineradicable pain from which ever since I have suffered is my failure to leave my two friends and their donkey cart so that I should walk home with Jody or, better still, give him my seat in that cart.

2

Growing up in Ballinrobe

LIFE in Athlone was orderly and uninterrupted until the dread day when, surprisingly, both of our parents took the train to Dublin, leaving us in the care of our eldest sister, Eileen. An expression of total desolation on both their faces as we met them at the station made it clear to all of us that something dreadful had happened. A Dublin medical specialist had confirmed that our father suffered from severe pulmonary tuberculosis. Although they did not know it at the time, my mother was also infected by the same disease. They in turn could have infected their children. I recall an infant sister, Annie, leaving our house in a tiny white coffin. She had died of massive pneumonic miliary tuberculosis. My eldest brother, Jody, in addition to a serious speech defect caused by an untreated cleft palate and a hare lip, developed a grossly deformed hunchbacked spine, infected by tuberculosis. He never grew taller than between three and four feet in height. Though he was intelligent, he could never attend school. Schoolchildren then would harass and jeer at the crippled and the disabled. Surprisingly my father, disappointed no doubt that his eldest son was deformed, was impatient with him. Jody was unwanted, crippled, and unable to fend for himself or communicate his simplest needs, except to the family; he was unable to mix with his peers. It is impossible to imagine the awesome humiliation and desperation of his life. I have never understood its purpose.

In addition to Jody and the infant who died, my mother, myself and two sisters became infected with tuberculosis and, with the exception of myself, all have since died. There was at that time no known worthwhile treatment. My father’s hardworking conditions had led to the infection in the first place, and with no light work available there was little prospect for his survival. It was simply a matter of months. He was sent away to Newcastle Sanatorium in Co. Wicklow where, as medical officer many years later, I read of the hopelessness of his case in his clinical notes.

Because there was no free tuberculosis service then, hospital care had to be paid for. Since there was no hope that the out-of-work patient could pay as his income had stopped with his work, or was simply inadequate, he would be sent home to die. In the process he would infect one or more of his loved ones. Discharge home from a sanatorium was, in effect, a sentence of death for the patient, and possibly for many members of his family. There were frequent examples of families, in desperate hope of saving the life of a loved husband, wife or child, being compelled to sell off their small farm or business in order to pay for medical expenses or hospital care. Consultants would agree to treat patients only so long as they had money; as soon as the money stopped, the treatment also stopped.

There is a tombstone in a graveyard by Newcastle Hospital, on which the names of nine young children of the same family are inscribed. Not one of the children was more than three years of age at death. Each name is recorded — Michael, Patrick, Mary, etc. It is of interest to note that the last name on this tombstone is the father’s name; he died at the age of eighty years. It is more than probable that this man, unwittingly, was responsible for the deaths of all his children.

From the day on which the consultant gave his diagnosis on my father, life for the Browne family followed a pattern which was a prototype for tens of thousands of families in our class in many countries. There was only the most rudimentary concept of what became known as welfare socialism throughout Europe. There was little or none in Ireland, where influential religious teaching rejected the ‘creeping socialism’ of state intervention in time of family need. I recall a curate in Newtownmountkennedy informing his flock from the pulpit on one occasion, when he had thundered ‘communism’ because of the local people’s attempt to feed the school children a hot mid-day meal in winter: ‘They can come to my back door and ask for it, if they need it’.

At times of impending disaster, young people appear to be preserved from understanding and appreciating the facts of what lies ahead for them. I continued to go to school and to deliver milk on my wonderful donkey-drawn equipage. My father had to stop work. Later still he was no longer seen around the house and was compelled to stay in bed. He was visited once by a doctor, and by a Franciscan priest on a number of occasions. Our aunt Bridie, a nurse, appeared more frequently at the house, and I began to notice a sad subdued mood within the family. I still had no idea that my father was dying.

Late one summer evening, in August, 1925, I was called to his bedroom. There was a crowd of people whom I did not know outside the room and around his bed. Though a son of the house I was unable to get to him, being crushed on the landing outside, too timid or unwilling to push my way in. There was an air of great solemnity among the grownups who, in the dark of my father’s room, murmured prayers in the awful rhythmic singsong rit

ual for those about to die. Someone had made him hold a lighted candle, and called for prayers for his soul and his happy death.

My father raised himself and, in a falsely strong voice, claimed ‘Joe Browne is not going to die’; then he sank back. Sometime during that night he must have died. It was possible that I was sent off to bed and had gone to sleep. I recited the Hail Marys with the others, not knowing why; I had not been conscious that he was dying or about to die. I did not know or understand about death. Later, in a dark corner in our big outhouse, I studied the oblong yellow pine coffin lid with its brass plate bearing the words, in black print, ‘Joseph Browne, aged fifty-four, R.I.P.’ The inexorable breaking up of the family had begun.

I sought to avoid walking behind the black horse-drawn hearse on its way to St. Mary’s Church, although Jody did. I have no idea why I felt this reluctance. Possibly I wished to deny his death or to recall him from the dead. He was buried the next day, as he had requested, in his family plot in Craughwell, Co. Galway. This was the first occasion on which I had met his brothers and sisters; I stayed with them for about a week and then returned home to Athlone.

The families of my parents had disapproved of their marriage and each of them had given up their own in order to be together and live out what came to be a tragically short life of mixed happiness and tragedy with each other. There was never to be a reconciliation. My father’s devoutly religious family would accept no responsibility for helping his young widow and her seven young children. My mother, who had absolutely no experience whatever to help her cope with the immense financial difficulties facing her, was compelled to try to make a home for her young family on a total of £100 insurance. There were no widow’s or orphan’s pensions, or children’s allowances. Our house belonged to the NSPCC, and the next inspector would need it when he took over.

My mother applied with no success for a local authority house in Athlone. For all her faith in God and his blessed Mother, she would send one of us children nearly every night with a drained teacup inside which the tea leaves lay, wrapped in a brown paper bag, to a local woman in Irishtown who would ‘read the cups’. She hoped that this woman would one day see a house for us in the tealeaves. Such a house never materialised, and she realised that she would have to take her family away.

She decided to return to Ballinrobe, under the commonly-held illusion that she could live out her life where she had happy memories of her young days. She had been born in Hollymount, just outside Ballinrobe, and moved into the town after her schooldays to work as a seamstress with a Mrs. Murphy, who owned a newspaper shop and dressmaker business. It was here that she, an exceptionally attractive country girl, met and fell in love with my father, a ‘comer-in’ from Athenry.

My mother was to find, on her return to Ballinrobe in her time of great need and deep distress, that she had not yet been forgiven. Other than the rent collector, I do not believe that anyone ever called or crossed the threshold of that newly-built small house except our childhood friends. They came, it is true, to the final auction sale some two years later, in order to bid for the remnants of her furniture and family possessions which were for sale. So, they divided up her few belongings between them.

The auction signalled the end of an Irish widow’s hopeless two-year struggle with her orphans, after my father’s death, in the new and pitiless Irish Free State. But that disillusionment was yet to come. Meanwhile, we packed up our possessions, and prepared to leave Athlone.

My memory of moving is of being seated beside Jody on the front cab seat of a lorry driven by a small Athlone man, whose face remains with me — black bushy eyebrows, sallow healthily-tanned skin, intelligent sturdy face, jet-black kindly eyes and a head of black curly hair on which he wore a cap. My particularly detailed memory of this man stems from the fact that he lost the way on our journey to Ballinrobe. It was a wintry night and we became very frightened. We had been sent on with the lorry driver to save train fares, and had travelled through the day with all our worldly possessions behind us in the lorry. It started to snow and the whole countryside was soon covered in snow. The worried look of the driver’s face is my last memory of that journey; through weariness I must have gone to sleep in spite of my fears. This journey was a momentous occasion, since it was the first time we had been separated from our mother in our lives.

Finally we reached Church Lane, Ballinrobe and helped one another to settle into our new home. The lack of welcoming visits from neighbours should have had its own ominous warning for my mother that she had seriously misjudged her people. All the members of her immediate family, the Cooneys, had long since left Hollymount for America on the emigrant ship, part of the great diaspora in the 1920s and 1930s. In her hopes for compassion, forgiveness or sympathy, my mother could have more usefully chosen the Sahara Desert for her last refuge.

I went to school, to the local Christian Brothers. They certainly taught us with great diligence, and with some effect, but for the most part they were enthusiastic religious zealots, whose sole purpose was to win young Irish boys and girls to Roman Catholicism in a united Ireland. They did not see any contradiction in fighting fiercely and winning partial sovereignty from the English while still proclaiming total subservience on all issues of serious social or political importance to a different faraway foreign ruler in Rome. ‘We will be true to thee ’til death’, they’d bellow at Croke Park.

These deeply religious men and women, using the word ‘religious’ in its loosest sense, had represented a remarkable phenomenon during the nineteenth century in Ireland, giving up their lives to promote a most powerful renaissance of Catholicism while at the same time sending hundreds of their numbers throughout the continents of Africa, Asia, the Americas and elsewhere as missionaries for the Catholic faith. They recognised the simple truth: ‘give us the child, and we will answer for the man’. Those who control education control minds, and thus control society.

There was no Gregorian chant in Ballinrobe. The general ethos was a powerful sense of angry nationalism and the demand that in all of us there must be inculcated a self-sacrificing patriotism. Singing classes were occupied with emotive patriotic songs mixed with the sweet laments for Ireland’s wrongs. A militant republicanism replaced the bland Free State ambience of Athlone. We knew and admired men ‘on the run’; unconsciously we braced ourselves for future sacrifice and struggle, probably even prison or death, ‘for Ireland’s freedom’. We played exclusively Gaelic games. I never possessed a hurling stick, since my mother could not afford to buy one, so I played Gaelic football.

This driving obsessive hatred for and of the English was systematically inculcated into our consciousness and rationalised for us into an embittered set of convictions. Hatred for Protestants, because their faith was of English origin, became an unpleasant feature of our young lives. A little jingle summed it all up for us — ‘Proddy, Woddy, ring the bell, when you die, you go to hell’. The hatred derived not solely from the occupation of our country but, according to the teaching of the Christian Brothers, from the destruction by the English of our Catholic faith.

Our history taught us to mourn, with intent to revenge, the savage torture by pitchcap and the rack of our patriot martyrs. Cromwell was simply a heartfelt curse word. As if to reinforce our introverted exclusive Irish nationalism, we had the ‘advantage’ of learning to speak the true Irish of the Gael.

While nearly all of us in the school were of poor English-speaking family background, already class distinctions were evolving. The children of successful business men or gombeens left early on to enter residential secondary schools. Some found their way into the diocesan colleges, the forcing ground for the Catholic priesthood. These church links between the Irish middle class and the priesthood help to explain the deeply conservative nature of the Irish Catholic church and of the new Irish state.

The children from the Gaeltacht areas were even more impoverished than ourselves, dressed in ragged misfitting clothes. They walked long distances bare-footed t

o school, with their hair uncombed and laden with lice, unwashed and dirty. Their teeth were rotten, their skin pockmarked with flea bites. In spite of the fact that here was the true repository of the cherished native language, they were not favoured by our militant nationalist Christian Brothers but treated with contempt as members of a lower order as the British had once treated all of us native Irish. I do not recall that they were shown any patience, concern, or understanding because of their illiteracy in English and their understandable difficulties in keeping up with the rest of us. At least one of them appeared to be chosen with little reason for the cruelly unbridled beatings which constituted Christian Brother discipline.

The brother who taught me first was a tall white-faced man, with thin bony shoulder blades protruding beneath his black cassock. He coughed violently and convulsively, and held to his mouth a white handkerchief which came away with fresh red bloodstains, all signs of tuberculosis. In the front row, I was unpleasantly close to the execution ceremony and truly dreaded the shock of it, though I myself was never a victim. The brother would grip my desk tightly with his hand until his fingers were blanched white in order to give himself support and added power. Then he carefully took hold of the visibly trembling fingertips of the defenceless victim and opened the dirty hand firmly. He took careful aim, and slashed out without restraint or pity. Each time, increasingly excited, beads of sweat gathering on his pale forehead, he raised the cane higher over his shoulder like an old-time thrashing flail; down it came again and again, increasing in speed and ferocity until it seemed to us that the tip of the cane appeared to whistle around in a full circle.

We could not understand how any of us could have fomented such an irrational anger or deserve such punishment. Yet I never saw any one of the beaten boys make any response, certainly no visible protest. The beaten mutilated hands were simply pushed up underneath the armpits, the sole concession to this savage and insensitive public assault on their bodies and on their self-esteem. Surely there was some private pain which the brother thereby tried to exorcise within himself. My greatest sympathy lay with the Irish speakers who could not have understood why they were so often chosen for punishment. For them there was an added isolation, the rest of us being unable to sympathise because of our inability to speak with them.

Against the Tide

Against the Tide